Il Kurdistan è un vasto altopiano tra Turchia, Siria, Iraq e Iran. Ma dalla fine dell’impero Ottomano quell’elemento da geografico è diventato geopolitico: esiste una etnia curda, non esiste uno stato curdo. Tuttavia anche senza una nazione quel popolo, che ha subito guerre, repressioni, migrazioni, vanta un “cinema nazionale” capace di raccontare l’identità, la vita, la storia, i luoghi.

Oggi uno dei registi curdi più interessanti e innovativi, anche per l’ironia usata, è Saman Hosseinpuor (Saqqez, Kurdistan, 23 gennaio 1993) che accetta, con grande disponibilità, di raccontarci un po’ del suo cinema.

Sei nato in una regione dell’Iran, ma sottolinei sempre, anche sul tuo sito internet (http://samanhp.ir), che sei un “independent kurdish filmmaker”. Quanto è importante per te essere curdo?

Penso che la vita e gli esseri umani siano impreziositi dalle loro differenze culturali, etniche e nazionali. La lingua che parliamo e in cui pensiamo, i costumi che seguiamo ed in cui siamo cresciuti sono fondamentali.

1. Saman Hosseinpuor

L’unicità di ciascuna persona dovrebbe essere importante per noi stessi. Questa originalità deriva dalla nostra cultura e dalla nostra storia. Per me, in quanto curdo, è importante mantenere questa unicità in ogni aspetto della mia vita includendola anche nel mio lavoro, mostrando al pubblico la vita dal mio punto di vista attraverso i film.

Come è nata la passione per il cinema? Quando hai capito che quella era la tua strada?

Quando ero bambino c’era una videoteca vicino a casa mia, dove andavo ad affittare i film. Parlai con il proprietario e gli dissi che la lente del mio lettore DVD era debole e che non leggeva alcuni dischi. Impiegavo venti minuti per tornare a casa, provare il CD o DVD e tornare al negozio. Ovviamente era una bugia. In quel tempo guardavo i primi dieci minuti del film e, se non mi piaceva, tornavo al negozio e lo sostituivo. Ho cambiato anche tre film in un solo giorno. Insomma il cinema mi ha sempre attratto, ma sono sempre stato “severo” e non mi piacevano tutti i film.

Oltre a questi giorni per me magici della mia infanzia, ho frequentato corsi di narrativa, scritto storie e partecipato a competizioni di livello locale. Grazie a questo percorso ho gradualmente familiarizzato con il cinema; con alcuni compagni produssi spontaneamente un film. Avevo 15 anni. Più tardi ho lavorato e recitato per un anno a teatro. Dopo quel periodo il cinema è diventato il mio interesse principale nonché un piacere costante. Un affare serio. Trovo lo scrivere storie affascinante, è la mia principale spinta.

2. 1-0 (2013)

Hai diretto il tuo primo film, 1-0 (2013), ad appena venti anni. Nel cortometraggio, in concorso in diversi festival, un barbiere inizia a tagliare i capelli ad un bambino intento a guardare una partita di calcio. Il ragazzo sogna un taglio alla Cristiano Ronaldo, ma, a causa del goal richiamato nel titolo, il risultato non sarà quello. Tutto in sessanta secondi. Hai una straordinaria capacità, perfezionata nei successivi film, di raccontare una storia in pochi minuti. Come ci riesci?

Tutto dipende dalla storia. Fin da bambino ho visto, sentito e raccontato storie. Sono abituato ai racconti, e mi viene naturale distinguere quelli interessanti ed attraenti da quelli brutti e noiosi.

Da ragazzo ho frequentato ogni singolo corso di narrativa e di sceneggiatura che fosse vicino a casa, e ho fatto del mio meglio per imparare. Continuo a studiare anche oggi, e credo che i miei sforzi non siano stati vani.

3. Autumn Leaves (2015)

Anche i successivi Autumn Leaves (2015), una poesia con protagonista una bambina e le foglie d’autunno, e Fish (2016), film ironico in cui un pesce rosso trova la salvezza nell’acqua di una dentiera, hanno ottenuto importanti riconoscimenti in numerosi festival. Per il cinema indipendente quanto sono importanti i festival?

Autumn Leaves inizialmente era solo una storia breve che scrissi per un giornale. Quando più tardi il cinema divenne la mia vita, mi resi conto di quanto quella storia fosse visiva e bella. Decisi così di farne un film. La storia di Fish, invece, mi venne in mente in macchina, pensando all’umorismo legato alla mancanza di acqua.

4. Fish (2016)

I festival sono sicuramente importanti per motivare e coltivare il talento. I registi sono prima di tutto indipendenti, poi sono attratti dal “body cinema” (cinema sperimentale, nda) e vanno ad influenzare il mercato e l’industria cinematografica. Senza festival, il ciclo dell’industria cinematografica si deteriorerebbe.

Penso quindi che i registi indipendenti siano una parte importante del mondo del cinema e, ovviamente, la bellezza del cinema sono questi lavori liberi che vengono realizzati con un pensiero indipendente.

La scorsa primavera, in piena pandemia, hai rilasciato gratuitamente The Man Who Forgot to Breathe (2017). Il film, realizzato ben prima del Covid 19, parte dalla storia di un uomo per mostrare un mondo in cui tutti indossano la mascherina. Hai doti profetiche?

5. The Man Who Forgot to Breathe (2017)

Ho fatto questo film nell’estate del 2016 e scritto la storia del 2015, cinque anni prima della pandemia del coronavirus. Una notte ho sognato di un mondo in cui tutti indossavano una maschera, non riuscendo a respirare. Lo trovai molto affascinante. Quindi iniziai a scrivere la mia storia. Provai a realizzare una “art story”, questo mio intento portò a rallentamenti, ma alla fine ho apprezzato il percorso.

Comunque no, non penso di essere un veggente o un chiromante. Vedo solo che l’uomo sta distruggendo l’ambiente in cui vive. Conseguenze terribili arriveranno a causa del cambiamento climatico, a meno che non lo si fermi. Mi rende davvero triste vedere gli uomini distruggere la Terra senza pensare al futuro.

Nel tuo film successivo, intitolato The Last Embrace (2018), una bambina cerca di far vedere un suo disegno ai membri della sua famiglia, ma tutti la ignorano distratti da smartphone, tablet, video game. La piccola troverà affetto sdraiandosi vicino al nonno da poco morto nell’indifferenza generale. In 4 minuti un “trattato” sull’alienazione del mondo attuale. Verremo “salvati” dalle nuove generazioni?

6. The Last Embrace (2018)

Questo è un punto molto importante. La nuova generazione è stata cresciuta dalla generazione precedente. Non ho una risposta, ma faccio del mio meglio per mostrare alcuni aspetti meno ovvi. Il mio lavoro è raccontare storie. E cerco di raccontare storie che rendano la vita migliore e trasmettano pace e tranquillità. Spero di riuscirci. Se anche solo riuscissi ad avere un impatto positivo su tre persone nel mondo, allora avrei fatto il mio lavoro, ed è abbastanza per me date le circostanze.

Su tematiche sociali anche i tuoi ultimi film, due bellissimi mediometraggi. In Slaughter (2018) un contadino è deciso a vendere la propria mucca per sopravvivere, ma il figlio è molto legato all’animale. In The Other (2020) un uomo, dopo la morte della moglie, sospetta che la donna abbia una relazione con un altro. Considerata anche la diversità dei tuoi film, sei più a tuo agio con opere ironiche, come 1-0 e Fish, o drammatiche come queste ultime?

7. Slaughter (2018)

Sto andando sempre più verso i film drammatici, ma non escludo altri generi… potrei già avere qualcosa in mente. Ma l’era dei cortometraggi è finita per me, e sto muovendo i primi passi verso i lungometraggi.

Ad esclusione di Slaughter tutti i tuoi film sono senza dialoghi. Come mai questa scelta?

Molto semplice: penso che le persone si sentano e capiscano gli uni con gli altri senza bisogno di parole. Solamente guardandosi, attentamente. Secondo me, il cinema è una arte visiva, e voglio raccontare la mia storia più che posso con sole immagini. Per me i dialoghi nel cinema sono uno strumento ausiliario, e non dovrebbero essere percepiti come principali e necessari.

Registi curdi del passato, come Yilmaz Guney (una sua foto si vede in The Other) o Bahman Ghobadi, ti hanno influenzato? Più in generale hai un regista e un film “preferito”?

8. The Other (2020)

La verità è che ho passato la mia infanzia con Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan e i film d’azione e di guerra. Anche se oggi non li guardo più, hanno avuto una parte importante nell’avvicinarmi al cinema.

Mi piacciono Yilmaz Guney e Bahman Ghobadi, rispetto molto il loro cinema, ma Kim Ki-duk con i suoi film ha avuto l’impatto per me più importante. Ho molti film preferiti, ma per me Kim Ki-duk vuol dire cinema.

I tuoi film hanno partecipato ad oltre 500 festival, incluse diverse rassegne italiane (Fabriano, Parma, Ischia, Cagliari, Matera) oltre al Golden Beggar del quale sei diventato anche membro della Giuria, e ottenuto quasi 50 premi in giro per il mondo. C’è un riconoscimento cui sei particolarmente legato?

I premi sono stati una grande motivazione e hanno dato energia al mio lavoro. Ma non credo ci sia un premio in particolare che mi sta a cuore. Forse il primo vinto, all’età di 16 anni, mi è molto caro perché mi ha stimolato ed ha rappresentato il primo impulso per diventare un regista.

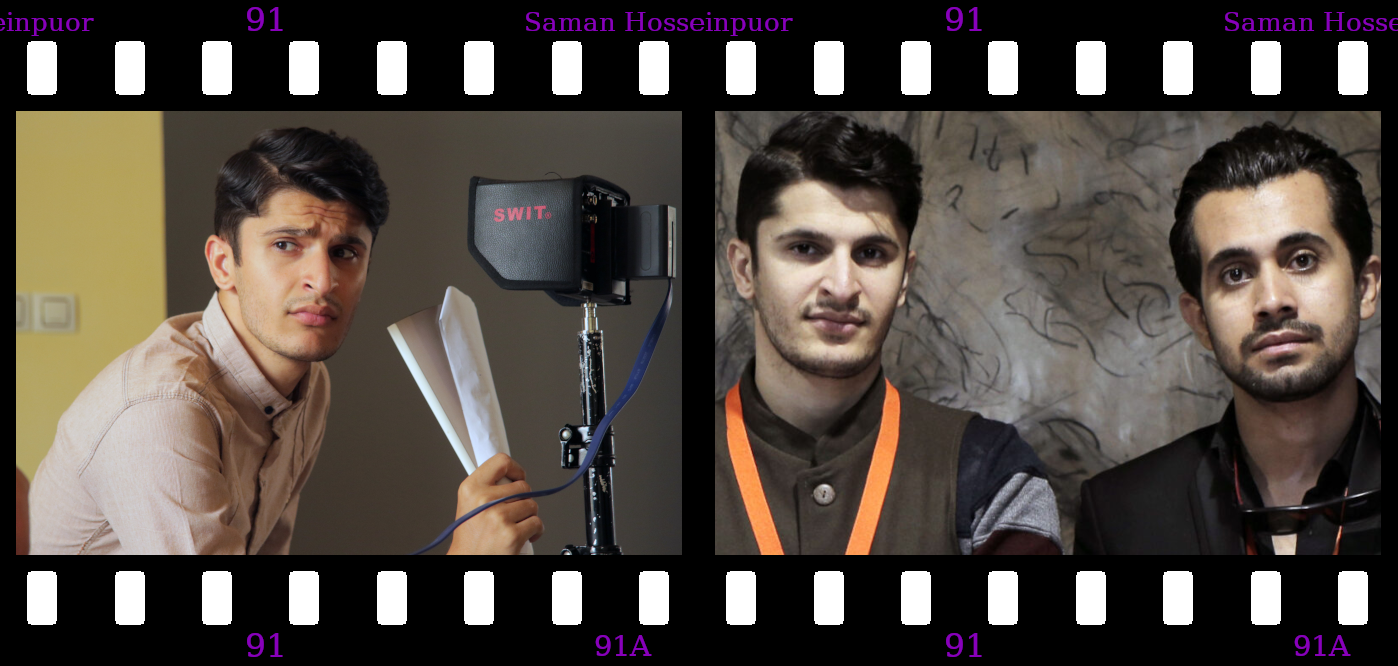

9. Samko Brothers: Saman Hosseinpuor e Ako Zandkarimi

Torniamo all’oggi. Hai dato vita, col regista Ako Zandkarimi, alla Samko Brothers. Ci vuoi raccontare meglio questo progetto? State lavorando ad un nuovo film: Congenital, storia di una ragazza costretta a sposare un vecchio uomo. Qualche anticipazione?

L’evento più importante della mia carriera nel cinema è stato conoscere Ako e creare i Samko Brothers. Siamo amici, ci conosciamo da quando siamo ragazzi e abbiamo lavorato insieme su molti progetti. Poi, un giorno abbiamo deciso di scrivere una sceneggiatura insieme, ci siamo emozionati e abbiamo capito che insieme lavoravamo meglio. Abbiamo quindi deciso di girare un film, chiedendo un prestito ad una banca. Nonostante le difficoltà il film ha avuto un ottimo risultato ed è stato selezionato in molti festival, così abbiamo deciso di continuare questo progetto insieme realizzando un altro cortometraggio che ci ha portato molta fortuna. Da quel giorno continuiamo a girare film insieme.

10. Saman Hosseinpuor

Siccome i nostri nomi sono lunghi, abbiamo deciso di sceglierci un nome artistico che ci distinguesse e che fosse semplice. I Samko Brothers si sono formati ufficialmente con la produzione di Congenital, che uscirà proprio in questi giorni.

Insieme abbiamo scritto i corti Rhino (2019), Blind chance (2019), Childbirth (2021), Ayesha (2021), Suitcase (2021) e diretto Slaughter (2019), The Other (2020) e appunto Congenital (2021).

Il cinema ha un grande valore per noi, perché ci permette di raggiungere un linguaggio comune e ascoltare le storie degli altri. Spero un giorno di poter venire in Italia per presentare uno dei nostri film e guardarlo con il pubblico.

redazionale

THE YOUNG KURDISH CINEMA AND THE SAMKO BROTHERS.

INTERVIEW WITH SAMAN HOSSEINPUOR

The passion for the “seventh art”: from the first films to projects with Ako Zandkarimi

Kurdistan is a vast land between Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. Since the end of the Ottoman Empire, a geographical element got a deep geopolitical meaning: a Kurdish ethnicity exists, but there isn’t a State. Despite the absence of a Nation, the Kurdish population has a fascinating national cinema tradition, able to narrate its identity, life and history.

One of the most interesting and innovative filmmakers is Saman Hosseinpuor (Saqqez, Kurdistan, 23 January 1993). Today I am thrilled to have a conversation with him about his work.

You were born in Iran, but you define yourself as an “independent Kurdish filmmaker”. How important is being Kurdish for you?

I think that life and human beings are beautified by their cultural, ethnic and national differences. What language we speak and think. What customs we follow and how we grew up is very important.

1. Saman Hosseinpuor

In my opinion, the originality of each person should be important for himself, and this originality comes from our culture and historical background, which I, as a Kurd, am very important for myself to maintain this originality in my life and include it in my works, and Show life to the audience from my own point of view through my films.

How did you discover your passion? When did you realize that it could have been your path?

When I was a kid, there was a video club near our house that I went to rent movies. I had talked to the owner of the club and told him that the lens of our DVD Player was weak and it did not read some CDs. So, I took 20 minutes from him to go home and try the CD or DVD and get back to him (well obviously I lied to him). I used this time to watch the first 10 minutes of the movie. That is, I would go home in five minutes and watch the first 10 minutes of the movie, and if I did not like it, I would go to the video club again in five minutes and I would change the movie. Occasionally I would change 3 movies. Cinema was attractive to me and of course I was strict and I did not like any movies.

In addition to these fascinating days of my childhood, I also went to storytelling classes and wrote stories and participated in local competitions. Gradually, I became acquainted with cinema in these classes, and we spontaneously made a film with some of my classmates. I was 15 years old then. And later I got acquainted with theater, and I worked and acted in the theater for a year, and it was after that that cinema became a constant pleasure and a serious concern. In fact, storytelling is fascinating, and that’s probably my only reason to keep going.

2. 1-0 (2013)

You were only 20 years old when you directed your first movie, 1-0 (2013). In the short film, a barber cuts a little boy’s hair, while the boy watches a football match. The boy dreams of Cristiano Ronaldo’s haircut. However, because of the goal you mention in the title, the hairstyle result will be different. Everything happens in 60 seconds. You have an extraordinary ability to tell a story in a few minutes. How do you do it?

The fact is that everything depends on the story. I have seen, heard and told stories since I was a child. And I have been accustomed to stories since I was a child, and I almost distinguish good and attractive stories from bad ones and boredom. When I was a teenager, I did not sit idle at all, and I went to every storytelling and screenwriting class that was close to our city and home, and I did my best to learn. Although I still try and study. But I think my efforts have not been in vain.

3. Autumn Leaves (2015)

In 2015 you released Autumn Leaves, a poem about a little girl and the autumn leaves, while in 2016 you directed Fish, a humorous story about a goldfish that finds safety in denture water. Both your movies obtained important recognitions in several festivals. How important are those festivals for the independent cinema?

Autumn Leaves was initially just a very short story I had written for a newspaper that was published, and later as cinema became more serious to me, I saw how visual and beautiful this story was and decided to make it. The story of the fish all came to my mind in a car, and I thought about how to humorously refer to the lack of water.

4. Fish (2016)

Festivals are definitely important to motivate and nurture talent. The fact is that filmmakers are first independent and later they are attracted to body cinema and influence the market and the film industry. If there are no festivals, the cycle of the cinema industry will gradually deteriorate, and I think independent filmmakers are an important part of the world cinema, and of course, the beauty of cinema is these independent works that are made with independent thinking.

Last spring, during the pandemic, you released The Man Who Forgot to Breathe (2017), for free. Despite filmed before the outbreak of Covid-19, it starts with the story of a world where everyone wears a mask. Are you clairvoyant?! Keeping it sober, how did the pandemic affect your activities?

5. The Man Who Forgot to Breathe (2017)

I actually made this film in the summer of 2016 and wrote the story in 2015. It can be said almost 5 years before Corona pandemic. One night I dreamed of a world where everyone wears a mask and has trouble breathing, and I was fascinated by what happened. So, I started writing my own story. I tried to write an art story, and of course my point of view caused the film to slow down a bit. Although I like it very much as a work.

But no, I do not think I am a clairvoyant or a fortune teller. The fact is that humans are expected to destroy their habitat soon. Worse things are on the way with global warming. Unless it is stopped. I am sad when I see Humans destroy the earth without thinking about the future.

In The Last Embrace (2018), a girl tries to show her drawing to the family, but everyone is too busy looking at smartphones, tablets and video games. She finds comfort laying down next to her grandad, dead in the general indifference. In 4 minutes, you manage to explain the topic of alienation in today’s world. Will the new generations save us?

6. The Last Embrace (2018)

This is a very important issue. The new generation has been raised by the previous generation; I do not have the answer. But as much as I can, I try to bring the lesser-known points before their eyes. You know, my job is to tell stories. Of course, I am telling a story that makes life better and invites people to peace and tranquility. I hope it works. Even if I have a positive impact on 3 people in this world, I have done my job and it is enough for me with these few facilities and financial constraints.

Your last movies treat social issues. In Slaughter (2018), a farmer wants to sell his cow to survive, but his son is very attached to the animal. In The Other (2020), after his wife passed away, a man starts to doubt her loyalty and suspects she had an affair. Considering how diverse your movies are, are you more comfortable with ironic pieces (like 1-0 and Fish), or dramas (like your last two)?

7. Slaughter (2018)

I think I’m trying to make drama films and I’m moving in that direction. Although it is possible to make genre films, I may have some ideas in mind. But that era of short films is over for me and I have started my steps towards feature films.

Besides Slaughter, all your films don’t have dialogues. Could you explain to us the reason for this stylistic choice?

It’s very simple. I firmly believe that human beings can feel and understand each other without talking to each other. Just look at each other, carefully. In my opinion, cinema is a visual art, and as far as I can advance my story with the image, I definitely do not use dialogue. In my opinion, dialogue in cinema is an auxiliary tool, and it should not be seen as a main and necessary tool. that’s how i have less dialogues in my films.

Have you been influenced by other Kurdish directors such as Yilmaz Guney (his pictures appear in The Other) and Bahman Ghobadi? Do you have a favorite director and a preferred movie?

8. The Other (2020)

Truth be told, my whole childhood was spent with Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan and action movies, although I do not see action and war movies now. But they probably played a bigger part in drawing me to the movies. I like Yilmaz Guney and Bahman Ghobadi and I have a lot of respect for their cinema, but Kim Ki-duk has had the greatest impact on me with his films. There are many favorite movies, I think that is enough to say Kim Ki-duk cinema.

Your films appeared in over 500 festivals. You became a judge at the Golden Beggar, and you won almost 50 prizes worldwide. Is it there one that is particularly dear for you?

Rewards have always been motivating and energizing to work with. But I do not think there is a special award that is dear to me. Maybe my first film award, which I received at the age of sixteen, is dearer to me because it invited me to make films and maybe it’s the first motivation to be a filmmaker.

9. Samko Brothers: Saman Hosseinpuor e Ako Zandkarimi

Recently, together with Ako Zandkarimi, you started the Samko Brothers. Could you please tell me more about this project? You are working on a new production: Congenital. Can you anticipate anything?

The best event of my working and cinematic life is getting to know Ako and creating Samko brothers. I had known him since he was almost a teenager and we had worked together on several projects and our friendship had been formed, until one day we decided to write a screenplay together and after the result we got excited and realized how much better we could work together. We decided to make a movie together. Although there were many problems, and although we made the film with a loan from a bank. But a good film came out of the water and with this film we went to many festivals and decided to make a film again and made a short film with another name, which was also a very lucky film for us. After that, we decided to make a new film again, and this path always continues.

10. Saman Hosseinpuor

Due to the long name of both of us in the credits and the media, we decided to choose an artistic and short name for ourselves that is both distinctive and short. The Samko brothers were officially formed with the production of the Congenital short film, and now that I speak to you, the congenital film is ready to be shown.

We have directed: Slaughter (2019), The Other (2020), Congenital (2021) and we wrote scripts of these short films together: Rhino (2019), Blind chance (2019), Childbirth (2021), Ayesha (2021), Suitcase (2021).

Cinema is very valuable to us because it is in cinema that we reach a common language and listen to each other’s stories together in peace. I hope that one day we will be able to come to Italy to screen our films and watch the films with the audience.

editorial

Immagini gentilmente concesse da Saman Hosseinpour

Images courtesy of Saman Hosseinpour